As Long As You Can Still Listen: The Criminalization of Migrant Boat Drivers in 2022

Publication date: Tuesday 10 January 2023

by the 'From Sea To Prison' project (ARCI Porco Rosso and borderline-europe)

"They will not eject you from history as long as you can still speak, they will not banish you to the past as long as you can still listen."

The poetic words of the Egyptian political prisoner Alaa Abd El Fataah pithily express the importance of getting the voices behind bars out, both for those of us who are outside and for those who are enclosed within. His words also seem appropriate to us as a way to represent the many Egyptian citizens who are held within Italian prisons, accused or sentenced - along with many others - for a crime that, in our view, is equally political: facilitating freedom of movement.

The war in Ukraine and the energy crisis swept across the year, underscoring the inevitability of movement, flight and struggle. Around 150,000 people risked the Mediterranean Sea to try and build their future on other shores, attempting to overcome a racist, colonial system made up of blockages and barriers. Of them, at least two thousand did not make it across alive. The arrests, trials and sentencing of boat drivers are a part of this European fortress: an enclosure that draws on criminal law as a method of exclusion and bloody oppression. The project that we have continued since the publication of the report From Sea to Prison in October 2021 focuses on developing solidarity networks and tools that can combat this process of criminalization.

As we wrote in the report, in the vast majority of these trials the accused have little or indeed nothing to do with the violent organizations and groups that people on the move are often forced to deal with during their journeys. More frequently than not, the accused have themselves been exposed to and exploited by such methods. Furthermore, we feel it is important to note that these organizations evolve and react to fill the gap created by European policies of closure, and are themselves the product of policies enacted, first and foremost, by Italy.

The Italian political context - which has been object of constant change but also, unfortunately, of significant continuities - represents the framework within which these struggles take place. The new government voted in over the Summer includes post-Fascists in the majority: this development has inevitably resulted in more attacks against people crossing the Mediterranean border and, obviously, anyone who helps them to arrive in Italy alive- whether these are the drivers of the boats or the NGOs rescuing people at sea. The words of the Prime Minister, Giorgia Meloni, tragically confirm this. Faced with a crisis with France, triggered by Italy's attempt to block the docking of NGO rescue ships that had rescued hundreds of people, she stated that it would be "better to single out boat drivers, not Italy." These hateful words nurture the demonization of people who have done nothing other than drive boats carrying people in flight across the EU border. They are an attempt to once again place the figure of the people smuggler at the center of the debate – as a universal scapegoat to lay the blame on for all the death and violence that takes place at Italy's marititme borders.

While these rhetorical attacks can be seen as one element in the ongoing symbolic war against the NGO rescue missions, the arrests of boat drivers and the practices enacted by Italian authorities and courts continue without change, as we demonstrate in this end of year report. The systemic nature of the arrests that we described in 2021 remains a constant, just as much as is the lack of any interest by successive governments to question the violence and inhumanity of Article 12 of the Immigration Act (facilitating irregular immigration), or at least to take account of the harsh and arbitrary manner in which thousands of people have been sentenced and imprisoned for this crime.

How Many Boat Drivers Were Arrested in 2022? And Who Are They?

Our systematic news monitoring reveals the dimensions and character of the criminalization of migrant boat drivers, including details that reflect changes both in the routes utilized by people on the move as well as in the ways by which Italy attempts to criminalize them and close Europe's doors in their faces.

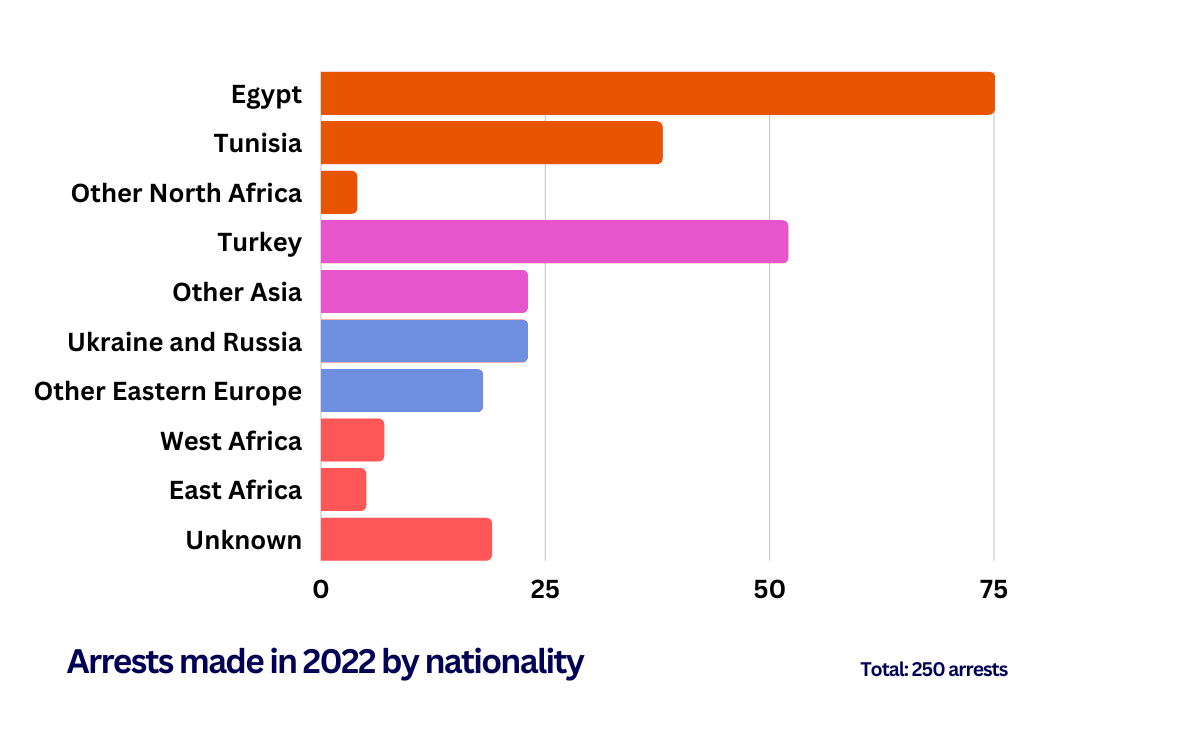

In 2022, we counted the arrests of 264 people following migrant landings. This figure is not scientific, but based on the news reported by journalists, above all in the Italian local press. Using this same method, we counted 171 arrests in 2021; in their annual report in April, the Italian police claimed to have made 225 arrests. If we maintain the same level of accuracy, we can estimate that around 350 people were arrested over 2022.

Given that 85,000 people arrived in Italy by sea over 2022 (according to data from the Italian Home Office), the number of arrests corresponds to one person for every 300 arrivals, a rate similar to 2021 and overall similar to the period 2014-2017. The nationalities of the arrested people, however, are very different from that same period. In the years following the re-opening of the Libyan route, many people from West African countries were arrested, adding up to around one quarter of all arrests. Over the least two years, however, we have counted only 10 arrests of people from West Africa.

This fall in the number of arrests of people from West Africa is partly due to known changes in the main nationalities of people choosing to migrate, but also due to the dynamics of the routes being utilized. The increased number of arrests of people from North Africa and Central Asia illustrates this. Indeed, the police arrested twice as many people from North Africa in 2022 as in 2021: we counted 118 arrests in 2022, in comparison with 61 in 2021. Over the last two years, as in previous years, the majority of these were Egyptian citizens. And indeed, the number of Egyptians who have risked the Mediterranean over 2022 was more than double that of 2021 (18,285 in comparison with 8,576, according to government data).

Another significant change between 2021 and 2022 has been the fall in the number of Ukrainian citizens arrested by the Italian police. In 2021 we saw 32 such arrests following landings; in 2022 we counted only 9. Ukrainian skippers have been fundamental for the arrival of people departing from Turkey, being expert sailors who know how to handle a boat for the difficult week-long journey across the Aegean Sea and up to the Italian coastline. With the outbreak of the war, Ukrainian men have been blocked from leaving their country, which has undoubtedly been a determining factor in the diminished availability of Ukrainian skippers. The importance of this route, however, has only intensified. Consequently, we have noted a doubling in the number of arrests of Turkish citizens (24 in 2021, and 52 in 2022) and Russian citizens (7 in 2021, 14 in 2022) as well as many more arrests of people from Asia in geneal: Syrians, Bengalis, and even people from landlocked countries, such as Kazakhstan and Tajikistan.

Our Casework

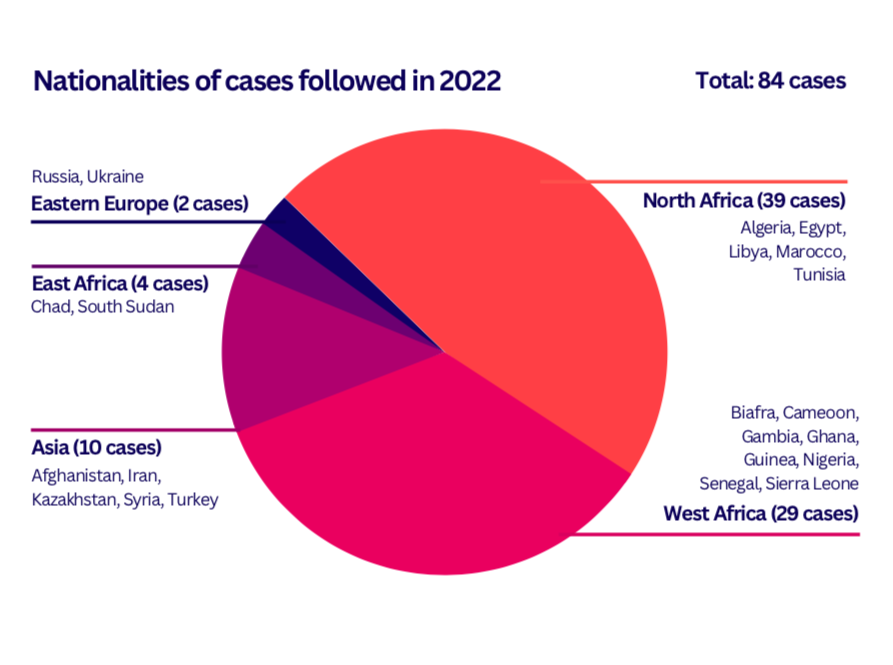

We are closely following the cases of 84 people who have been criminalized as boat drivers, 54 of whom are currently in prison. Around one half of them are from North African countries, while about one third are from West Africa. Other cases are of people from Asia, East Africa and Eastern Europe. Among these there are also two female prisoners whose cases we are following, one from Russia and the other from Ukraine.

We got in touch with these people through a growing network that is increasingly aware and active on the issue of criminalized captains. We have also met many people who are not currently detained – whether still on trial or having completed their sentence - through the migrant solidarity project at ARCI Porco Rosso, our community space in Palermo.

An important way that we keep people up to date about their legal situations is through an exchange of letters with prisoners. These letters also – and perhaps more importantly still -- provide a moment for encounter and an opportunity for prisoners to express themselves. The messages we receive are extremely varied, from stories about daily life in prison to sharing important moments and memories. Sometimes they're tragic, when every word makes you feel the injustice of a life lived behind bars, other times they are light-hearted or even funny, and manage to make us almost forget the physical barrier that separates us from the people we correspond with. For example, on several occasions the letters are from young men who write to us about the heart-breaking separation from their girlfriends following their sentencing, as well as telling us about the huge difficulty these young women also have to face in their own countries, caught in a limbo of waiting for an imprisoned man. But others have also shared jokes and drawings with us, and always send the warmest of greetings to everyone who continues to struggle alongside them for their freedom.

We have also followed different trials over the last few months, whether in Palermo, Agrigento or Messina. Being present in court has allowed us not only to support the lawyers in communicating with their clients during a frequently complicated process, but has even been a chance to think through legal strategies together with them, and the best course of action for the different situations. Furthermore, court is also sometimes a site to come across further cases which otherwise might have remained hidden from sight. Similarly, we have tried to be present around deportation centers (the Italian C.P.R.), the non-places of administrative detention when, unfortunately, many boat drivers end up for a period of confinement following their release from prison, simply because they do not have Italian documents - or because as ex-prisoners they are automatically deemed to be 'socially dangerous'. In 2022 we followed the case of a boat driver from Biafra, who had a pending asylum request, but was deported to Nigeria anyway, without his case being heard by a judge, and we have reports of many Tunisian captains who were put through the same ordeal . Unfortunately sometimes not even being found innocent is a ticket out of a deportation center: we followed the case of a Libyan citizen who, despite being acquitted of all charges, after years of building a full life in Italy was arbitrarily detained in a deportation center because he was deemed to be "socially dangerous" on account of the very crime from which he had been found innocent - a social stigma that transformed into outright persecution.

A fundamental way to challenge this dominating narrative that demonizes boat drivers is to bring out and amplify the voices of the people who are detained or facing trial. To this end, over recent months we have shared our knowledge with journalists, who have published news stories and carried out important investigations. The working group Lost in Europe investigated the question of minors accused of being boat drivers, publishing for the BBC among other platforms. The Post International published an extensive article about the case of two Turkish citizens sentenced to 12 years in prion; we are now in contact with both the accused and their lawyers. Lorenzo D'Agostino wrote about the case of Helmi El Loumi for the Italian newspaper Domani, a young Tunisian man blamed for the horrendous shipwreck of November 2019, sentenced to eight years in prison and with whom we are in regular correspondence. Furthermore, the situation in Italy has been compared with that in Greece and in the UK by different journalists: for the New Humanitarian in English, and for La Liberation in French. All of these articles and others can also be found on our website.

Growing a Support Network in Italy

We believe that building and nurturing networks in Italy that can collaborate on issues related to the criminalization of migration is fundamental for supporting people criminalized as boat drivers. The people we are in touch with who have been arrested and detained and the research we do to support defense investigations are spread out across Italy. In 2022 we took part in a number of events around the country to meet activists and professionals engaged in related issues, from anti-racist networks and humanitarian NGOs to lawyer’s networks and groups campaigning around prisons and detention.

We started conversations on this topic and introduced our work in Catania with the city’s Antiracist group Rete Antirazzista Catanese, in Messina with the local branch of ARCI ‘Thomas Sankara’, and at the Ghorba Fest in Pozzallo. These occasions provided us the opportunity to open discussions on the criminalization of captains and to talk with a range of people, communities and associations in different cities. On a related note, we collaborated with the bar associations in Palermo and in Agrigento to organize legal trainings for lawyers, delving into issues connected to Article 12 of the Immigration Act from a juridical standpoint. The training in Palermo is available online thanks to Radio Radicale.

We’re also very glad to have taken part in the conference ‘The Borders of Solidarity’ organized by the Legal Clinic at University Roma 3, ASGI and Mediterranea, to connect and exchange experiences on different examples of how the “facilitation of irregular immigration” is criminalized. It was also very important for us to be invited to the conference ‘(Im)mobilities and borders along the Adriatic routes’, again organized by ASGI, and the University of Bari, which investigated features and challenges associated with migration routes across the Adriatic and Ionian seas. The conference was was extremely helpful in fostering our connections with activists in the south of Italy and allowed us to better understand what happens at many different ports of disembarkation outside of Sicily. This knowledge later turned out to be very useful also when NGO ships had to start disembarking at ports that were increasingly distant from the Central Mediterranean, such as Bari, Taranto and Salerno.

Our work would be impossible without the involvement of well-established networks across Italy. First and foremost is the national federal organization ARCI , of which the association Porco Rosso in Palermo is a part. We have forged a strong relationship with the HQ in Rome to bring the issue of criminalization under the scope of the national hotline’s socio-legal support; we also participated in Arci’s Sabir festival in Matera and took part in the ongoing conversation with groups and actors that are engaged on the same issues.

We also traveled to meet people who fight for prisoners’ rights, to bring their attention to the captains’ situation and to exchange best practices. An example of this is the great initiative La Prigione e la Piazza a series of cultural events and discussions about different aspects of prison and society, organized around an itinerant book fair. The initiative took place in several Italian cities, including Naples and Palermo. Here we had the opportunity to also meet the other groups who organized the initiative, such as the activists of Napoli Monitor and the Comitato Via Cipressi; and we participated in the Assemblea Nazionale Carcere (the National Assembly on Prison) which was held at the Ex Centrale social centre, in Bologna.

We also set up a collaboration with the national offices of Antigone (the regional section of which has already been working with us since last year), and with the office of the Civil Ombudsperson who supported our work with prisoners. And we have had the opportunity to get better acquainted with CRIVOP, a national network of volunteers working in prisons, which is active in many detention facilities in providing support and attention to inmates. It was very important for us to get a chance to meet the volunteers at their national meeting in Palermo.

Our work connects the sea and the prisons, the world of migration and freedom of movement to that of detention, two worlds of activism that all too frequently remain disconnected . To develop networks in both these spheres this year has allowed us to better grasp the connections and the potential posed by a joining these struggles together. For example, we think it’s important to call the attention of the groups and associations active around prison to what is happening in deportation centers, as detained people often consider these places to be even worse than prison. For this reason, and to demand the closure of these horrendous places of segregation, we participated in a protest against detention centres in Turin, and along with other Sicilian groups that were monitoring the situation of the CPR in Caltanissetta, we protested to support the many detained people who were resorting to desperate efforts to regain their freedom.

Last but not least, we are proud to have renewed our collaboration with the Sea Watch Legal Aid Fund, and to also havereceived vital support from the Safe Passages fund, thanks to which we can continue our focused research work and activism with the dedication it deserves.

From Sea To Prison

10 January 2023.