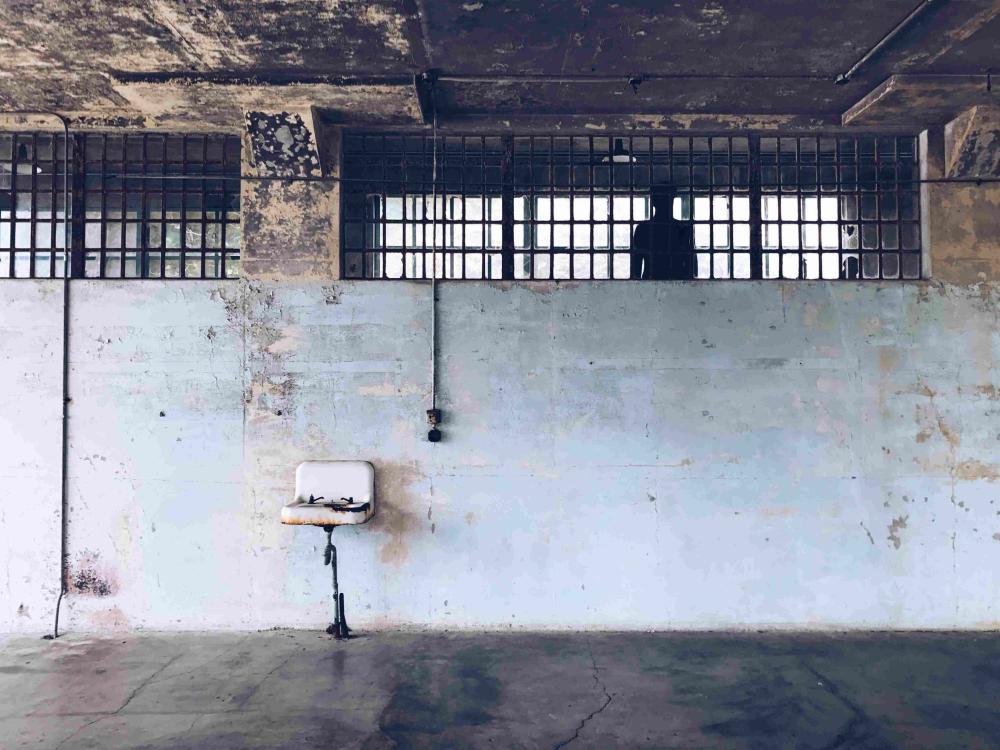

Three more prisoners on hunger strike - the prison emergency never ends

by Alessia Candito published in La Repubblica

Three Palestinians Fares, Walid and Ayman, are in prison in Catania, Sicily on suspicion of being smugglers. Walid can no longer get up, Fares can no longer walk, and only Ayman manages with great effort to reach the interview room. "He was a big man. When I first saw him,” murmurs lawyer Grazia Palazzo, “I hardly even recognised him.” Once again, in a Sicilian prison people choose hunger and thirst strikes in an effort to make their voices heard. And although it has been little more than a month since the death of two inmates in the prison of Augusta, who died after a long protest that nobody was informed about, again the news of these strikes has only filtered out of prisons thanks to lawyers and associations, who managed to inform the guarantor of the rights of prisoners yesterday.

For days now, Walid, Fares and Ayman have been refusing food, water and even the drips which have been offered in an attempt to hydrate them. Their condition is worsening. "Until they are heard, they are not willing to undergo treatment," explains their lawyer. “They do not understand why they are in prison. They do not understand why the investigators did not believe their words but gave credit to others. They do not understand why trying to escape from daily violence and abuse in Libya is considered a crime. They didn't choose to leave Gaza, they say, they were forced to. They couldn't stand hunger and bombs any longer, so they left, faced months in Libya where they worked as slaves and realised that there was no future for them there. So, they went in search of one together with about a hundred other people, on board a dinghy, with a weak engine that, they say, everyone took a turn trying to restart. They were rescued by a merchant ship, which took them on board until a Coast Guard patrol boat arrived and brought them to Catania.

Here, they thought the nightmare was over. Instead, three of their fellow travelers, all from Bangladesh, pointed the finger at them. Investigators found no evidence to back up these accusations, but what they did take as incriminating was that the men were in possession of 'a mobile phone and a duffel bag with personal belongings (including cigarettes, perfume and gel) and clothing soaked in petrol'. One of them, it is argued, had ‘US dollars ($400) in cash, which would have allowed them to return home to facilitate further trips or otherwise connect with others in their home country or in Italy'. The evidence? None, in fact the sum was immediately released again. The protagonists of this story only learned what was happening afterwards, as their lawyers and the associations that are following them have informed us.

Branded as clandestine in spite of possessing regular passports and in one case even a certificate from UNRWA, the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees, they were arrested and taken to prison. Papers and documents in a language they understood were only provided later. Once behind bars, there was also no one to ask for help in a shared language. "This is not an isolated case. In Italy there are almost a thousand people in prison because they have been accused of violating Article 12 and branded as boat drivers,' explains Richard Braude of Arci Porco Rosso, an association in Palermo, which has been following these cases for years now. "Often the evidence is weak and entirely circumstantial, but there is no alternative to detention for them because they have no residence in Italy". Some structures, run by associations or non-profit organisations, make themselves available for house arrest. But they have very limited capacity. As a result, most remain in prison, not just prisoners of the facility, but also of linguistic and interpersonal isolation. This is a bubble that the 'Porco Rosso' activists have been trying to break for some time by maintaining ongoing correspondence with the inmates. "It is a way to help them keep in touch with the world. One of these guys,” says Braude, “has been in prison in Trapani for a long time, he keeps telling us ‘my only wish is to be able to meet you', but in this and other cases our requests to do so have fallen on deaf ears.” Some associations, such as the Astalli Centre, manage to get through those bars, providing at least clothes, basic necessities and comfort. 'One of the most frequent requests,' explains Stefania, who met the three men, 'is to be able to call their family members.

They are entitled to have a phone card, but it is useless because it has no credit and has to be recharged, and we cannot do that. Family members certainly also can't do that, many of whom don't even know whether their loved ones have survived. Ayman did manage to contact his family through his lawyer. He left ten children in Gaza. "Free my dad, Mr. Judge", they chant in a video appeal sent to his lawyer, in which his wife can be heard saying: "We live in a house that is barely a shelter because my husband is only a worker, if he were a smuggler we wouldn't be living like this". But the petition for their release has failed and as a result Walid, Fayes and Ayman have stopped eating and drinking. Informally, people are trying to provide these men with all possible assistance, as has filtered from the prison. Among the first services needed is psychological assistance, but with language as a barrier it becomes near impossible. "In Italy, there is on average less than one mediator per prison. And of course they do not speak all the languages of the world,' 'Porco Rosso' members note. The hunger strike is a universal 'cry', but too often even that goes unheard.