From Sea to Prison: Across the Whole Terraqueous Globe

From Sea to Prison project

First quarterly report 2023 Arci Porco Rosso and borderline-europe

In the days following the maritime massacre at Cutro, in which at least 93 people lost their lives, the Italian government decided to announce new measures that will deprive thousands of people of their documents, make legal entrance into Italy even more difficult – and further criminalize migrant boat drivers. Announcing this vortex of invisibility, death and imprisonment, the Italian President, Giorgia Meloni, added that for her government:

“This doesn’t only mean cracking down on smugglers we find on the boats, but also on the smugglers behind them. […] We’re used to Italy going and looking for migrants across the whole Mediterranean. What this government wants to do is go and look for smugglers across the whole terraqueous globe.”

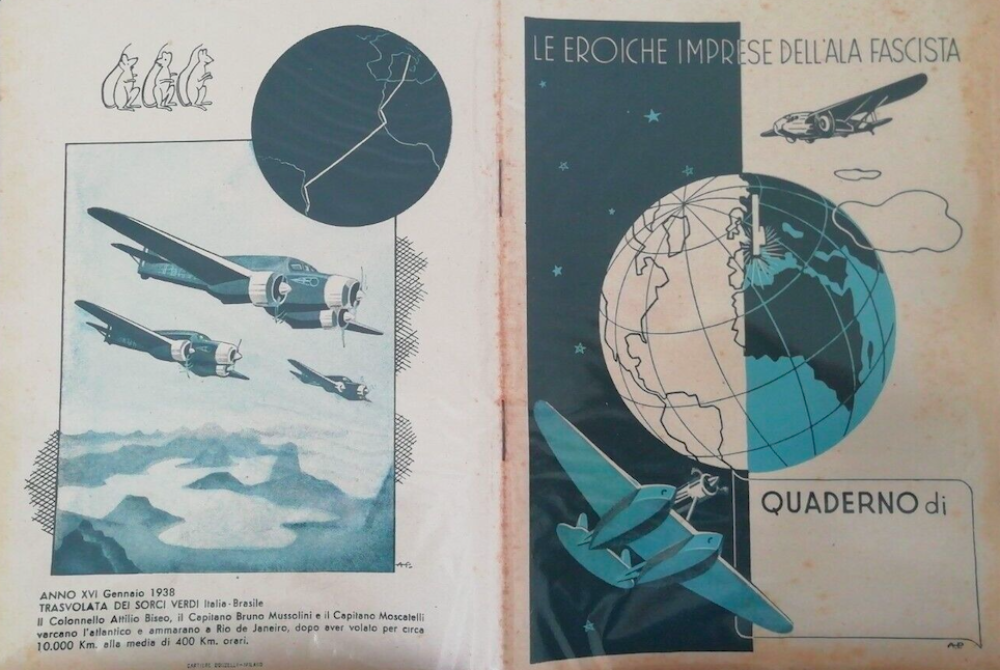

With a pompous flourish that wouldn’t be out of place in a speech by Mussolini, Meloni introduced new, harsher laws that, unfortunately, are completely in line with policies of border closure followed by Italian governments of every stripe for decades. To cite but the most scandalous example, Italy gave carte blanche for its Anti-Mafia investigators to go and look for “the smugglers” on every side of the Mediterranean following the Lampedusa shipwreck of 3 October 2013, culminating in the embarassing extradition of an Eritrean refugee from Sudan who had nothing to do with international people smuggling but was mistaken for a Libyan crime boss.

While Italy gears up to launch other international missions of this kind, the government can always keep “looking for migrants”, the perfect scapegoats for the mass death caused by closing the borders. These same old dynamics are repeating themselves inat Cutro. The three people arrested following the tragedy claim to have nothing to do with any smuggling organization, and that they can prove it - as they have explained to their lawyers, with whom we are collaborating to ensure their right to a fair trial and a proper defense. Those arrested include a Kurdish man who has fled Turkey, while another is a teenager who lost his cousin in the shipwreck, currently detained in a juvenile prison, in a country where he doesn’t speak a single word of the language. He still hasn’t been allowed to identify his cousin’s body. Another suspected boat driver was identified among the corpses; a further suspect is missing (and possibly dead). The final suspect was stopped in Austria and has been waiting extradition for over a month. In the meantime, nearly all of the possibile witnesses have left Italy, even before they can be cross-examined in preliminary hearings. Up till now, these are the results of the police operations following the disaster.

The series of requests for prosecution presented by civil society organizations in Rome and Crotone all point instead to the culpability of government ministers and the Italian Coast Guard. Indeed, it has already emerged in the first pre-trial hearings against the boat drivers that three hours went by between the shipwreck and the arrival of the rescue boats. This is despite the fact that there was air presence not only by the Italian Coast Guard but also the EU border agency, Frontex, who were monitoring “the whole terracqueous globe” from the sky, with the all-seeing eye of empire. But they left the people to die all the same, following a twisted logic of making arrests first – and protecting human lives later.

Cases and Court Hearings

The Italian police have claimed that over 2022 they arrested almost 350 people who they identified as “boat drivers and smugglers” – a number that matches the estimate we made in January. And while arrests continue at every landing, those arrested over the years continue to arrive in court for sentencing. Over the first few months of the year we attended a number of these trials. Unfortunately, most of these ended in appalling jugdgements.

- For the past 18 months we have followed the criminal trial of ‘Lamin’, a young Gambian man who has always claimed - right from the moment of his arrest - that he has never driven a boat in his life. In March the court in Messina sentenced him to 10 years in prison.

- The former magistrate of Kabul, Ahmad Jawad Mosa Zade, was sentenced to 7 years in prison by the court in Locri, Calabria. His lawyer had submitted important evidence to the court demonstrating that he had fledg Afghanistan because of the work he had carried out for state prosecution against the Taliban - but it seems that the court disregarded this.

- The appeals court in Palermo lacked the courage to significantly amend the sentence issued one year ago by the court of Agrigento in relation to Ahmed, a young man from Chad; they, simply reduced the sentence from 6 years and 8 months detention to 5 years and 5 months.

- The Court of Siracuse sentenced two Russian citizens, a man and a woman, to 4 years in prison. The couple were arrested in August last year, and accused of driving a boat carrying 100 people fleeing Afghanistan, Iran and Iraq. Both claim they were not the drivers. Yet even if they had been, we can’t help but ask the question: how do we think these refugees could have reached Europe safe and sound without someone driving the boat?

Fortunately, we have also witnessed some great victories. A man from Camerun with whom we had been exchanging letters for months was finally been acquitted by the Court of Agrigento, after almost 1 year in prison. His co-defendant, however, was sentenced to 4 years in prison. Another brilliant moment was when 10 people were finally acquitted of all charges by the Court of Palermo, which accepted the argument that some of the defendants had been forced to drive the boats from Libya to Italy and thus had acted out of necessity, ann argument that their defense lawyer had been making since 2016 (the others were found to not have driven the boat in the first place). Those acquitted include four people who are part of our community here in Palermo. We have followed them throughout this seven-year ordeal, supporting them through the constant postponement of the hearings, a situation that forced them into a legal limbo, with a significant effect on their ability to obtain documents in Italy.

Anti-Mafia Experts

The renewed political and press attention to the issue of boat drivers over the last couple of months has also presented an important opportunity to amplify the voices of people who have been criminalized – the true experts. Among these we highlight the words of Buba, Mohamed and Vasilij in Sicily (link in English), interviewed for Essenaiziale, of Timur in Calabria, interviewed for La Stampa; of Ibrahim, interviewed for Italian TV; of Diouf, currently hosted at the Baobab center in Rome, who hopes to re-open his trial; and of Bakary, interviewed for Valigiablu.

We have also been interviewed by the press, including by Giansandro Merli for il manifesto, by Simona Buscagflia for La stampa, by Rosita Rijtano for Lavialibera and by Luca Rondi for Altreconomia. In the wake of the disaster inat Cutro and the government’s propaganda against boat drivers, a series of authoritative comments have been published on the issue. Among these we would like to pick out the interventions by Gian Domenico Caiazza (President of the Italian union of criminal lawyers, who amply cited our work), by Gianfranco Schiavone (former president of the Italian immigration lawyers’ association) and by Cinzia Pecoraro for the magazine Io Donna (a lawyer with an important experience of these trials).

The popular novelist and screenwriter Roberto Saviano gave our activist research an important platform on his social media channels. While we appreciate the gesture, we would nevertheless like to make a small comment about his analysis. While no doubt attempting to reveal the corrupt relations between Italy and powerful figures in Libya (and the horrendous effect this alliance has on the lives of people trying to cross the Central Mediterranean), unfortunately Saviano muddles up different terms. He oscillates between ‘boat driver’ and ‘smuggler’, ‘smuggling’ and ‘human trafficking’, creating new and unhelpful categories such as ‘the real smuggler’ and ‘driver-smuggler’. We believe it’s important to be careful about how these terms are used, and avoid a semantic confusion which is often purposefully encouraged in order to shift the blame for border deaths away from the decisions of Italian and European politicians, maximizing a narrative that criminalizes people on the move. And with a certain success.

Deaths at sea, however, will not end by hunting down boat drivers, nor by sealing new agreements with other countries – such as with Erdoğan’s Turkey or Saïed’s Tunisia – in order to hunt down people smugglers “across the whole terraqueous globe”. It will not even end if the “real smugglers” in the countries of departure are somehow magically all captured and subjected to an exemplary punishment. As with any market, so long as there is a strong necessity, someone will step forward and offer a service, probably utilizing means that are even more dangerous than the current ones – an evolution which we have already seen for decades. Death at sea and at borders more generally will only end when Itlaly and the EU change their border policies, not only through inevitably selective “humanitarian” corridors, but by allowing everyone to circulate and reach their destinations freely and securely - and not only those who have the strongest passports.

A Network spanning from North to South

Campaigning for freedom for the political prisoners of this unjust system is not just a struggle in the Italian South. Ironically, criminalization knows no borders. Over the past months we’ve met people all over Italy who have are engaged in antiracist and anti-carceral struggles, from north to south. Some of them have decades-long experience on criminalization and the prison system, while others are approaching the issue for the first time.

We went to Turin to learn from the city’s long-standing networks against deportation centers, places where captains are often forcibly brought when released from prison, and to know more about the criminalization of ‘passeurs’ and activists along the Italian-French border. We connected with squatted social spaces that struggle in solidarity with prisoners, including the anarchist prisoner Alfredo Cospito, and against the strict isolation regime imposed on him and many others. We thank the people from the Ex Lavatoio squat and the Metamorfosi collective for hosting us, and all the people who intervened in the discussion, especially those who bravely shared their personal experiences.

On the other end of the country, we travelled up the Ionian coast to better understand the dynamics of criminalization in Calabria, the work carried out by defense lawyers and the challenges faced by criminalized people upon their release from prison. During our trip we met with activists, lawyers, humanitarian workers and journalists active across the region. We thank the Nuvola Rossa collective in Villa San Giovanni, the ARCI committees in Reggio Calabria, Cosenza and Crotone, the activists from Antigone, Nessuno Tocchi Caino, and the LasciateCIEntrare network, the Dambe So hostel in Rosarno, the Calabria University Prison Campus, and the lawyers from ASGI.

Among the many issues we heard about in Calabria, we were often made aware of a very serious lack of linguistic interpretation, even to the extent of hindering the course of trials, or indeed the crucial communication between detainees and their lawyers. We also heard about the near-total absence of healthcare in prisons in Calabria, highlighted by a number of disturbing individual accounts of malpractice as well as horrendous living conditions. These violations of fundamental human rights contributed to the death of Oleksandr Krasiukov, a Ukranian citizen who died on February 17 in the Catanzaro prison following a medical emergency. Oleksandr had been sentenced to 3 years in prison only 24 hours after arriving in Italy. He died in a prison that has documented failings, and as the consequence of dynamics that are still being investigated. We want to express our solidarity and condolences to his mother, who moved to Italy after the outbreak of the war, in part to be closer to Oleksandr. We stand in solidarity with her, and demand truth and justice for her son.